Fast & Flawless

- Published: April 30, 2004, By Edward Boyle, Contributing Editor

Spectratek is converting thin-gauge holographic films at high speeds, thanks to new equipment from Stanford Products.

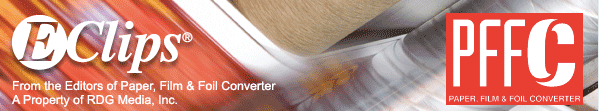

Terry Conway, a director of Spectratek Technologies, says packagers really have only two essential concerns when marketing their products: “How do I draw attention to my product, and how do I differentiate my product from dozens of competitors on store shelves?”

The answer for a growing number of consumer products companies, says Conway, is through holographic packaging film. Not surprisingly, that's exactly what Spectratek has been delivering for more than 20 years. Now, thanks to the recent installation of a high-speed slitter/rewinder and a Doctor Machine from Stanford Products, the Los Angeles-based manufacturer is meeting those needs faster and with better quality than ever before.

“People ask, ‘Why do holograms sell?’” says Conway. “Humans instinctively respond to color and kinetic movement. If you put a hologram on a shelf or on someone's desk, people are just naturally drawn to the product. In today's busy world, holographic film draws the customer's attention to your product, thereby directly increasing its sales.”

Application Explosion

Holograms were introduced more than 40 years ago as a niche product. During the 1980s, they were used for security applications. This was because of high manufacturing costs caused by the extreme difficulty of producing holograms and companies' limited production capacities. In the early 1990s, manufacturing costs began to drop and holograms were being widely used as premiums and promotions. By the late 1990s, manufacturers were producing holograms on both wider-width and thinner-gauge films. Consequently, the commercial applications virtually exploded like a starburst engraved on the holographic film itself.

Yet, as the base substrates have gotten thinner — from 2 mils 20 years ago to 48 ga today — the process of converting the polyester, polyvinyl chloride, nylon, and oriented polypropylene films typically used as the base material has required greater care and precision on the part of converters and their equipment. As with many converting operations, often slower line speeds have been the surest way to maintain registration and product integrity.

However, the recent installation of two pieces of Stanford finishing equipment — a 40-in. (web width) Model 142 LT Doctor Machine and a 70-in. (web width) Model 3038 slitter/rewinder — has greatly enhanced Spectratek's ability to maintain product quality while converting thinner-gauge films at high speeds.

The Doctor Machine is designed to handle light-tension materials, such as extensible films and other tension-sensitive materials. It can reach speeds of 1,000 fpm with maximum rewind and unwind diameters of 30 in. It is capable of trimming using shear, razor, or score-cutting methods.

The 3038 slitter/rewinder is designed to operate with a range of substrates, including film, laminates, paper, nonwovens, vinyl, cellophane, and pressure-sensitive (p-s) stock at speeds to 2,000 fpm. It can slit using razor, shear, or pneumatic-score methods. The optional roll pusher combined with a roll unloading device, both of which are installed on the Spectratek unit, help speed changeover times and reduce operator labor.

Eyeing a Growth Market

Prior to installing the two new pieces of Stanford equipment, Spectratek relied on two older Stanford slitters, Models 334 and 338, that actually were designed for running p-s materials far heavier than the unsupported 48-ga and 92-ga materials the company uses for the vast majority of its holographic films.

“In choosing both the Doctor Machine and the slitter/rewinder, we were primarily focused on being able to run thinner-gauge films, because that's where the growth in our market is,” says Conway. “I was looking at whether these machines could handle thin-gauge material and wind it with the proper uniform tension, without wrinkling the material, while maintaining good edge walls. The first decision I needed to make was whether to buy used or new. This decision proved easy. The new generation of slitter/rewinders is so much more productive, given the higher running speeds. The second decision was which equipment manufacturer to buy from. After much research and many trials, we chose Stanford because of the ease of operation, the easy off-load, and other productivity factors.”

Conway said he was particularly impressed with two features of the slitter: the four touchscreen operator monitors, which are positioned at key points on the unit to provide the operator more mobility in monitoring production, and its overall quick-change capabilities. Changeover times from job to job and roll to roll are reduced through the use of cantilevered rewind shafts and a shaftless unwind.

In addition, the optional roll pusher has proven to be “a tremendous labor-saving feature,” Conway says. “The operator just pushes a button, and the machine does the off-loading. So, you have a labor-saving factor and an employee-safety factor. The four operator screens give you the ability to walk around the machine and adjust speed or tension while it is running, rather than just being at the back of the machine adjusting settings after a lot of material already has been wasted. And the cantilevered rewind shafts and shaftless unwind make roll loading and unloading far more efficient.”

The process of manufacturing holographic films begins with the image being embossed onto film using one of Spectratek's custom-made embossers, in widths of 28, 41, 56, and 65 in. Film suppliers include SKC America, Toray Saehan, Mitsubishi, and DuPont. The film is then corona treated on one of four Pillar Technology lines before being metallized on a 65-in. Galileo vacuum metallizer to add reflectivity. The company often outsources its rolls to be laminated. The finished product is then slit on the Stanford machines to widths from 1-65 in. at speeds to 1,300 fpm.

Niche No More

Niche No More

The trading card industry became the first high-volume consumer application of holograms as companies such as Topps and Upper Deck began using them to produce specialty baseball cards in the early 1990s. “We literally produced billions of holographic decals for the trading card industry,” notes Conway. The ability to manufacture holograms in roll rather than sheet form made the process far more economical, and as a result, the use and popularity of commercial applications such as product promotions and novelty stickers greatly expanded.

Although the base material itself may be delicate, the holographic films can be coated and laminated for use in a variety of harsh environments and ultimately can be found in countless end products, some more unusual than others. In addition to stickers and trading cards, holographic films are a critical component in tens of millions of folding cartons for everything from toothpaste tubes to cigarette cartons to DVD and video packaging. They're used to produce millions of metallized balloons, as window films and material glazing on office buildings, as tabletop laminates, as room dividers in hotels and restaurants, and more.

“The growth of holograms came with the ability to produce them in a continuous roll process,” notes Conway. “It continued to branch out into more industries, such as folding cartons and flexible packaging, as a result of the lower cost-per-unit sales price and the manufacturers' ability to produce it on even thinner and wider-width materials.”

Use of holographic materials also began to expand as the manufacturers of holographic materials began offering an even greater variety of patterns. Spectratek, for example, has developed seven new patterns in the last two years alone that have broadened the market for holographic materials and greatly expanded its own sales base. The company now offers 31 distinct holographic patterns.

Two years ago, Spectratek broke from its traditional prismatic patterns to introduce the SpectraSteel line of imitation metal packaging films being used to convert laminates into premium packaging for industrial products. The product, which projects an image of brushed finished aluminum, galvanized metal, or stainless steel, has become instantly popular with manufacturers of tools and hardware as product packages and point-of-purchase sales tools.

“We've been producing holographic film for 20 years, and our products traditionally have appealed to a certain segment of the marketplace,” notes Conway. “Over the years we've heard comments like, ‘Boy, I wish you had something that fit my product line.’ Our response was the SpectraSteel line, and we've had great success with that.”

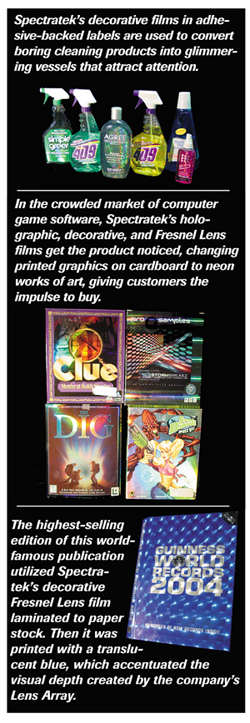

To further expand its product line, last year Spectratek introduced its Fresnel Lens Array product line, which offers a completely different look than SpectraSteel or even traditional holographic films. The company-patented generation process delivers film with not only three dimensions but also much greater visual depth. That product has been used on champagne cartons, video game boxes, the cover of the 2004 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records, and movie posters for the sci-fi hit The Matrix.

“The look is completely different,” Conway says of Lens Array. “It gives the appearance of depth, and you can also see your reflection in it. And the lens is something that people haven't seen. Manufacturers are always looking for what's new, what's hot, but holographic materials have been out for 20 years. They've been looking for something new to increase sales, and the new lens patterns definitely have triggered a lot of new interest.”

This year, Spectratek introduced eight engraved patterns that offer a subtle, rich feel, as a marked alternative to foil. While not prismatic, they offer the package designer another set of unique designs and looks.

“What we have done is start to develop additional artwork categories beyond traditional holographic design, which is itself a continual growth market,” explains Conway. “We see lots of other applications out there for different types of embossed patterns, i.e., SpectraSteel, Lens Array, and engraved patterns.”

Conway says the diversity of its product line is matched only by the quality and consistency of its end products. Starting with the generation of its holographic images, Spectratek's production process delivers holographic material that offers consistent image quality and brightness in a range of film thicknesses, all critical to making sure they function flawlessly during their customers' converting process.

To meet the increased demand for its new products, Spectratek recently more than doubled its manufacturing facility, from 28,000 sq ft to 72,000 sq ft, resulting in a 300% increase in its embossing capacity. Those end products ultimately are sent to laminators, printers, and converters that typically convert the holographic films into labels, cartons, and specialty materials. And, says Conway, the number of uses — and users — of this former “niche” product continues to expand.

“People ask, ‘How long is the holographic industry going to continue?’” notes Conway. “‘Is it just a fad?’ People have been asking that question since the 1980s, and it's still getting into more and more commercial applications. It's selling very well, and it's been that way year after year.”

CONVERTER INFO

Spectratek Technologies

5405 Jandy Pl.

Los Angeles, CA USA, 90066;

888/44-COLOR; spectratek.net

SUPPLIER INFO

Stanford Products stanfordproductsllc.com

SKC America skcfilms.com

Toray Saehan toraysaehan.co.kr

Mitsubishi Polyester Film m-petfilm.com

DuPont Polyester Film dupont.com

Pillar Technologies pillartech.com

Galileo Vacuum Systems galileovacuum.com